Editor’s Note: Originally published in 2013, this article used the concept of randomness to spotlight a seemingly minor risk in eDiscovery: the one-percent chance of error in each manual data transfer. In 2025, that risk is no longer theoretical. With 60% of breaches involving a human element—and third-party involvement doubling year-over-year to 30% according to the latest Verizon DBIR—the compounding failure potential of every data “hop” has become a measurable, recurring threat.

This updated edition revisits the original theory through the lens of today’s legal and cybersecurity landscape, where Generative AI introduces silent transfer risks, and new regulations like the DOJ’s Data Security Program impose real liabilities for cross-border data exposure. For eDiscovery professionals navigating complex workflows, the takeaway is urgent: fewer transfers, more platformization, and an architecture that shrinks the surface area where human error, misconfiguration, or regulatory missteps can occur.

From Lab Errors to Data Lakes: The One-Percent-Per-Hop Problem in eDiscovery

Information - 92%

Insight - 94%

Relevance - 90%

Objectivity - 92%

Authority - 90%

92%

Excellent

A short percentage-based assessment of the qualitative benefit expressed as a percentage of positive reception of the recent article from ComplexDiscovery OÜ titled, "From Lab Errors to Data Lakes: The One-Percent-Per-Hop Problem in eDiscovery."

Industry News – eDiscovery Beat

From Lab Errors to Data Lakes: The One-Percent-Per-Hop Problem in eDiscovery

ComplexDiscovery Staff

The Hidden Probability

Leonard Mlodinow, in his seminal work The Drunkard’s Walk – How Randomness Rules Our Lives, explored how probability theory applies across domains from finance to forensics, arguing that understanding randomness can reveal insights that remain hidden to those relying on intuition alone. Mlodinow, a physicist and mathematician, used his book to share an intriguing overview of the presentation of DNA evidence in criminal trials, noting a critical gap in how probability was often presented to juries.

He observed that while DNA experts regularly testified that the odds of a random person’s DNA matching a crime sample were one in a billion, they often omitted a critical variable: the probability of human-based error. Labs make errors. Samples are accidentally mixed, swapped, or contaminated. As Mlodinow noted, experts estimated these human-based transfer errors at roughly one percent, though he acknowledged that “since the error rate of many labs has never been measured, courts often do not allow testimony on this overall statistic.” This hidden variable significantly affected the “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard: if the chance of a lab error is one in a hundred, stating the chance of a random match is one in a billion becomes statistically misleading.

This concept forces a critical question for today’s legal professionals regarding the probability of human-based error in the transfer of data between the disparate technologies used in electronic discovery. When this article was originally hypothesized in 2013, we estimated that manual data transfers carried a roughly one percent risk of error. In 2025, that estimate is no longer just a thought experiment, as industry data and breach analyses consistently validate that the human element is often the most fragile link in the data chain.

The Reality of Modern Risk

The 2025 Verizon Data Breach Investigations Report, which analyzed over 22,000 security incidents and 12,195 confirmed breaches, found that 60% of breaches involve a human element—whether through social engineering, credential abuse, or simple misconfiguration. More striking still, third-party involvement in breaches doubled year-over-year to 30%, underscoring the risks introduced every time data crosses organizational or system boundaries. For eDiscovery professionals, this means that misconfiguring a cloud storage bucket, sending a file to the wrong recipient, or mishandling a load file transfer is not an edge case—it is a statistically predictable failure mode.

Furthermore, studies on manual data entry and migration suggest that without automated verification layers, error rates in manual data entry often range between 1% and 4%. In an eDiscovery matter involving millions of records, a one percent error rate does not simply mean a few corrupted files; it can mean thousands of privileged documents inadvertently produced or critical metadata fields stripped during a supposedly routine export procedure.

To evaluate this modern risk, one must consider the rule for compounding probabilities. In the context of eDiscovery, this risk compounds with every “hop” data takes between systems, so that each additional transfer introduces a new point of failure, compounding the cumulative risk of error across the project lifecycle.

The Math Behind Compounding Error

The compounding effect is not intuitive, which is precisely why it catches organizations off guard. If each transfer has a 1% chance of introducing an error, the probability of completing n transfers without any error is (0.99)ⁿ. Conversely, the probability of at least one error occurring is:

P(error) = 1 − (0.99)ⁿ

Consider a typical siloed eDiscovery workflow with five transfer points: collection to staging, staging to processing, processing to review platform, review platform to production set, and production to delivery. With a conservative 1% error rate per hop:

- 1 transfer: P(error) = 1 − 0.99 = 1.0%

- 3 transfers: P(error) = 1 − (0.99)³ ≈ 3.0%

- 5 transfers: P(error) = 1 − (0.99)⁵ ≈ 4.9%

- 10 transfers: P(error) = 1 − (0.99)¹⁰ ≈ 9.6%

At the higher end of industry estimates—a 4% error rate per transfer—the math becomes alarming:

- 3 transfers: P(error) = 1 − (0.96)³ ≈ 11.5%

- 5 transfers: P(error) = 1 − (0.96)⁵ ≈ 18.5%

- 10 transfers: P(error) = 1 − (0.96)¹⁰ ≈ 33.5%

In a complex litigation matter with ten transfer points and a 4% per-transfer error rate, you face roughly a one-in-three chance that something has gone wrong somewhere in the chain. This is not a theoretical concern—it is the statistical reality underlying countless privilege breaches, metadata failures, and chain-of-custody disputes.

The Evolution of the Data Journey

In a traditional, siloed approach, a firm might use one tool for collection, export the data to a hard drive or a different cloud server for processing, and then export it again to a separate review platform. This creates multiple distinct transfer points involving manual mapping of load files and physical media handling. In this scenario, the risk is not just corruption but security: every time data is landed to be moved, it creates a temporary copy, often in a shadow IT environment like a paralegal’s local desktop or an unsanctioned file-sharing site that lacks the security controls of the primary platform.

The industry attempted to solve this through the “best of breed” approach, connecting disparate tools via API. While this reduces the physical handling of data, it introduces logic errors. If an API mapping is misconfigured by a human administrator at the start of the project, that error can propagate across the entire dataset instantly. While automation reduces the clumsiness of manual transfers, it does not eliminate the risk of configuration failure or the need for rigorous validation and monitoring. Notably, the 2025 DBIR’s finding that third-party involvement in breaches doubled to 30% suggests that API integrations and vendor handoffs may themselves be a growing attack surface.

The most direct mathematical way to drive transfer-specific risk toward zero is through the adoption of a unified data model, often referred to as platformization. In this approach, data is ingested into a single encrypted data lake and then remains in place, with analytics, processing, review, and production implemented as different lenses or services applied to that same corpus. By eliminating or radically minimizing the act of moving data between systems, the probability of transfer error as a distinct failure mode is effectively removed from the equation, even though other risks—such as ingestion error, mis-tagging, or reviewer mistakes—must still be managed.

The Tradeoffs of Platformization

However, unified platforms are not a panacea. Organizations considering this approach must weigh several legitimate concerns against the transfer-risk benefits.

Vendor lock-in represents perhaps the most significant strategic risk. When all data resides in a single vendor’s ecosystem, switching costs become substantial—not just financially, but operationally. A platform that performs well today may lag behind competitors in three years, yet the cost of migration may be prohibitive. Organizations must negotiate carefully for data portability guarantees and standard export formats.

Single points of failure shift rather than disappear. While transfer errors are eliminated, the consequences of a platform-wide outage, security breach, or data corruption event are amplified. If your review platform goes down in a siloed architecture, you can still access your collected data elsewhere; in a unified model, a single failure can halt all operations. Robust SLAs, redundancy guarantees, and incident response protocols become critical.

Best-of-breed functionality may be sacrificed. A unified platform optimizes for integration, not necessarily for excellence in any single capability. Organizations with specialized needs—advanced analytics, particular AI models, niche data types—may find that a platform’s “good enough” tooling underperforms compared to dedicated solutions. The question becomes whether the risk reduction from fewer transfers outweighs the capability reduction from consolidated tooling.

Pricing leverage diminishes once an organization is deeply embedded in a platform ecosystem. Competitive pressure that keeps costs down in a best-of-breed environment evaporates when switching costs are high. Long-term contracts with price escalation caps and periodic market-rate adjustments should be negotiated upfront.

The right answer varies by organization. High-volume practices handling routine matters may benefit most from platformization’s efficiency and reduced error surface. Boutique firms handling complex, high-stakes litigation may prefer best-of-breed tools with rigorous validation protocols at each transfer point. Most organizations will land somewhere in between, consolidating where possible while maintaining specialized tools where necessary—and applying the compounding probability framework to evaluate each architecture decision.

The AI and Regulatory Multiplier

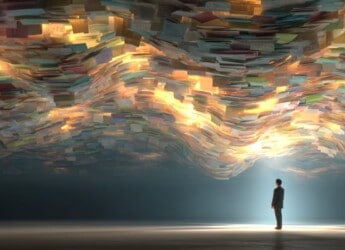

The definition of transfer itself has mutated in the age of Generative AI. The original 2013 analysis could not foresee the rise of Large Language Models, which have introduced the new risk of data leakage. In 2025, the risk is not just moving data between eDiscovery tools, but the temptation to move data out of secure environments into public models for summarization or translation. Research from Harmonic Security, a data protection vendor specializing in AI security, found that 8.5% of employee prompts to generative AI tools contained sensitive data in a Q4 2024 study. (It should be noted that Harmonic’s analysis was conducted among security-conscious enterprises already using their monitoring solutions, which may not reflect broader industry behavior.) The 2025 DBIR corroborates this concern, finding that 15% of employees routinely access generative AI tools on corporate devices, with 72% using non-corporate email accounts to do so. This represents a silent transfer where a legal professional might copy a privileged snippet into a public chatbot to fix grammar, effectively exposing confidential client information to a third-party system.

Compounding this technological risk is the new regulatory landscape. Transfer risk today carries a heavier penalty than just data spoliation. The U.S. Department of Justice’s Data Security Program implementing Executive Order 14117 went into effect on April 8, 2025, and restricts the transfer of certain categories of sensitive personal data—including genomic, biometric, financial, geolocation, health, and other bulk datasets—to specified “countries of concern” (currently China, Cuba, Iran, North Korea, Russia, and Venezuela) and covered foreign persons. A manual or poorly mapped data transfer that accidentally routes data through a server in a restricted jurisdiction is no longer just a technical error but a potential regulatory violation. This raises the stakes for any siloed or opaque approach where geographic data residency and data flow paths are harder to track than in a unified, compliance-certified cloud platform that explicitly documents and constrains data locations.

Removing the Dice

Leonard Mlodinow taught that hidden probabilities rule our lives, often leading us to underestimate risk. In eDiscovery, those probabilities now span not only lab-like handling of digital evidence, but also cloud architectures, API mappings, AI prompts, and geopolitical data transfer rules. The one percent error that seemed negligible in 2013 has been magnified by the scale of modern data, the proliferation of integration points, and the severity of 2025 regulatory consequences.

The industry’s shift toward unified platforms represents one disciplined approach to removing an entire category of avoidable risk from already complex workflows—though it introduces its own tradeoffs that must be carefully evaluated. The goal is not to find a perfect solution, but to make architectural choices with clear-eyed understanding of the probability trade-offs involved.

For legal and eDiscovery professionals, the practical implications are straightforward: minimize the number of hops in the data journey, treat every GenAI prompt involving client information as a transfer decision, map data flows against data localization and EO 14117-style restrictions, and give preference to architectures that keep data in one governed place while moving only views, workflows, and models. By moving from transferring data to unifying data—and by recognizing AI prompts and cross-border paths as part of the transfer calculus—organizations do not just improve the odds; they narrow the surface area where luck can intervene and, as much as practicable, take the dice off the table.

News Sources

- Manual Data Entry Errors (Beamex)

- 67 Data Entry Statistics For 2025 (DocuClipper)

- The impact of Human error in data processing (Fluxygen)

- From Payrolls to Patents: The Spectrum of Data Leaked into GenAI Copy (Harmonic Security)

- Mlodinow, L. (2008). The drunkard’s walk: How randomness rules our lives. Pantheon Books.

- Manual Data Entry And Its Effects On Quality (Quality Magazine)

- National Security Division | Data Security (United States Department of Justice)

- Office of Public Affairs | Justice Department Implements Critical National Security Program to Protect Americans’ Sensitive Data from Foreign Adversaries (United States Department of Justice)

- 90 FR 1636 – Preventing Access to U.S. Sensitive Personal Data and Government-Related Data by Countries of Concern or Covered Persons (GovInfo)

- 2025 Data Breach Investigations Report (Verizon)

- Drunks, DNA and Data Transfer Risk in eDiscovery (ComplexDiscovery)

Assisted by GAI and LLM Technologies

Additional Reading

- Kinetic Cybercrime: The Terrifying Shift from Hacking Code to Hacking People

- Europe’s Ransomware Crisis: Converging Criminal and Nation-State Threats Redefine the Risk Landscape

- Infostealer Logs Expose 183M Credentials: Strategic Implications for Cybersecurity

- When Anonymity Becomes a Weapon: Inside the Takedown of Europe’s Largest SIM Farm Operation

- When the Sky Falls Silent: Europe’s New Hybrid Threat Landscape

Source: ComplexDiscovery OÜ