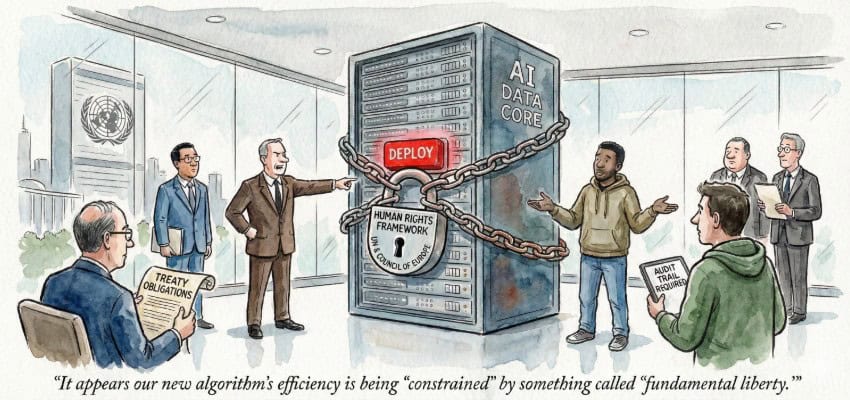

Editor’s Note: Human rights are rapidly moving from philosophical principles to enforceable obligations and concrete expectations in AI governance. With the United Nations and the Council of Europe setting the tone, cybersecurity, information governance, and eDiscovery professionals must now treat rights‑based compliance as a core design requirement. This article identifies the emerging international architecture—from the Pact for the Future and its Global Digital Compact annex to the new UN AI Panel and Dialogue and the Council of Europe’s binding AI Convention—and offers practical guidance on aligning AI systems with evolving norms for transparency, oversight, and redress.

Content Assessment: From Principles to Practice: Embedding Human Rights in AI Governance

Information - 95%

Insight - 94%

Relevance - 93%

Objectivity - 92%

Authority - 90%

93%

Excellent

A short percentage-based assessment of the qualitative benefit expressed as a percentage of positive reception of the recent article from ComplexDiscovery OÜ titled, "From Principles to Practice: Embedding Human Rights in AI Governance."

Industry – Artificial Intelligence Beat

From Principles to Practice: Embedding Human Rights in AI Governance

ComplexDiscovery Staff

Human rights in the age of artificial intelligence are no longer an abstract concern; they are fast becoming an operational constraint on how data is collected, analyzed, and turned into evidence. For cybersecurity, information governance, and eDiscovery teams, the United Nations’ emerging AI rights framework is shifting from background noise in New York conference rooms to a live factor in tooling decisions, regulatory interactions, and cross‑border contentious matters.

This article outlines how global rights‑based frameworks are evolving—and how cybersecurity, governance, and legal professionals can prepare systems, policies, and documentation accordingly.

The UN’s Digital Compact: A Rights‑Based Vision for AI

The Global Digital Compact, annexed to the Pact for the Future adopted at the Summit of the Future in September 2024, sets out a shared vision for an “inclusive, open, sustainable, fair, safe and secure digital future for all.” It commits states to foster digital cooperation that “respects, protects and promotes human rights,” including through enhanced governance of artificial intelligence, closing digital divides, and developing interoperable data governance approaches. The Compact is a non‑binding political declaration under General Assembly resolution A/RES/79/1, but it consolidates a set of expectations that states have endorsed at the head‑of‑government level.

From Resolutions to Infrastructure: UN Bodies and Their Mandates

One practical expression of those expectations is the decision to establish both an Independent International Scientific Panel on Artificial Intelligence and a Global Dialogue on AI Governance. The General Assembly operationalized that move on 26 August 2025 by adopting resolution A/RES/79/325, which sets out the terms of reference and modalities for the Panel and the Dialogue. The resolution mandates the Panel to provide evidence‑based assessments on AI’s opportunities, risks, and societal impacts, and tasks the Dialogue with convening governments and stakeholders annually to share best practices, discuss international cooperation, and support responsible AI governance aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals.

For practitioners, the key point is that these processes are explicitly anchored in the Global Digital Compact’s human‑rights‑centric framing of digital governance, rather than in a purely technical or industrial‑policy agenda. A sensible immediate step for any organization using AI in security operations, compliance analytics, or review workflows is to inventory where those systems intersect with rights‑sensitive contexts—such as surveillance, employment, or content moderation—and to ensure that governance documentation addresses explainability, oversight, and redress in language that can be understood by regulators and courts.

The First Binding Treaty on AI: Europe Sets the Legal Bar

The Convention requires parties to ensure that activities across the lifecycle of AI systems are fully consistent with human rights, democracy, and the rule of law. Its core obligations echo familiar data‑protection principles—legality, proportionality, transparency, accountability, and privacy by design—but now apply explicitly across AI system design, operation, and oversight.

As of early 2026, several states, including the United States, have signed the Convention. The Convention will enter into force after a three‑month period following ratification by at least five signatories, including at least three Council of Europe member states—a threshold not yet met at this writing. Whether the United States will proceed to ratification—which would require Senate consent—remains uncertain, as no ratification process has yet been completed. Regardless, the Convention’s principles are already shaping expectations among trading partners, regulators, and counterparties in cross-border matters.

For cross‑border investigations and eDiscovery, this means treaty‑level language on explainability, oversight, and access to effective remedies may increasingly be invoked in arguments about AI‑enhanced review, document prioritization, or risk scoring.

Human Rights Language, Real‑World Impacts

Civil society and UN human‑rights bodies are working to ensure that AI governance is explicitly framed in terms of impacts on internationally protected rights, not only in terms of “safety” or “ethics.” Article 19, for example, has stressed that the UN’s Global Digital Compact and AI‑related resolutions should prioritize human rights and sustainable development, and has pressed states to refrain from using AI systems that cannot be operated in compliance with human rights law or that pose undue risks, particularly to vulnerable people. The Freedom Online Coalition’s 2025 joint statement on AI and human rights similarly highlights risks such as arbitrary surveillance, discriminatory profiling, and online harms, and calls for risk assessments, human oversight, and effective redress mechanisms.

The UN Human Rights Office’s B‑Tech Project has gone further by publishing a taxonomy of human‑rights risks connected to generative AI. That paper maps harms from generative AI products and services onto specific rights, including freedom from physical and psychological harm, equality before the law and protection against discrimination, privacy, freedom of expression and access to information, participation in public affairs, and rights of the child. It emphasizes that the most serious harms being observed are impacts on rights already guaranteed under international human rights law, and that existing state duties to protect rights and corporate responsibilities to respect them should be applied directly to generative AI.

For cybersecurity and information‑governance teams, this rights‑based turn has concrete implications. AI‑driven monitoring and anomaly‑detection tools may need to be documented not only in terms of technical performance, but also in terms of their impact on privacy, non‑discrimination, and freedom of expression, especially when used in workplace surveillance or content moderation contexts. A practical way to integrate this is to extend existing data‑protection impact assessment processes into AI impact assessments that explicitly consider which rights could be affected, how, and what mitigations—such as human‑in‑the‑loop review or clear appeal mechanisms—are in place.

Practical Steps for Cybersecurity, IG, and eDiscovery Teams

Beyond the text of these instruments, practitioners and commentators are already drawing operational implications. Analysts of UN resolution A/RES/79/325 see the Panel and Dialogue as platforms that will promote transparency and accountability, capacity‑building for states with fewer resources, and openness and interoperability in AI models and data. This mix aligns closely with what many enterprises are already pursuing internally: more explainable models, better documentation, and clearer lines of responsibility when AI informs high‑stakes decisions.

For US-based teams, these international developments do not displace domestic frameworks—such as the NIST AI Risk Management Framework, emerging state laws in Colorado and California, or sector-specific guidance from the FTC, EEOC, and FDA—but they increasingly inform them. Organizations with multinational operations, global clients, or exposure to cross-border litigation should expect international human-rights norms to surface alongside domestic compliance obligations.

For cybersecurity operations, this suggests that AI‑assisted tools used for intrusion detection, fraud prevention, or behavioral analytics should be implemented with explicit human‑rights safeguards in mind. That can mean logging AI‑generated alerts and decisions in ways that allow later audit, ensuring that algorithmic outputs are not the sole basis for punitive measures without human review, and testing for discriminatory impacts in datasets and thresholds. It also means being prepared to explain, in clear and non‑technical terms, how a given system works, what data it uses, and what measures exist to prevent unjustified intrusion into private life.

Information‑governance leaders are likely to face growing expectations that AI‑relevant policies—on retention, classification, and access control—reflect not only national privacy laws but also international commitments to cultural and linguistic diversity, inclusion, and non‑discrimination. In practice, that may involve asking vendors precise questions about training data sources, bias mitigation practices, and whether systems can be configured to provide user‑facing explanations and contestation channels in languages that match the affected populations.

For eDiscovery and investigations, the Framework Convention’s insistence that AI use remain consistent with human rights and the rule of law provides a shared reference point when parties discuss the defensibility of analytics tools. Legal teams may increasingly be expected to show that AI‑assisted review platforms allow for meaningful human oversight, provide sufficient logs to reconstruct how key decisions were reached, and include mechanisms to correct or challenge outputs that appear biased or erroneous. One practical tactic is to align internal AI‑governance playbooks with the themes reflected in A/RES/79/325 and in rights‑based guidance: transparency about AI’s role in workflows, investment in staff capacity to interrogate AI outputs, and a preference for systems that support audit and interoperability over opaque black boxes.

Toward a Rights‑Based Discipline for AI Governance

This article reflects developments and public documentation available as of January 2026, including the Pact for the Future and its annexes, resolution A/RES/79/325, and early commentary on the Council of Europe Framework Convention. The picture that emerges is not yet a fully harmonized “global” AI regime, but it is already a recognizable architecture: a UN‑anchored political compact that centers human rights in digital governance, a pair of new UN mechanisms to translate those commitments into ongoing expert advice and dialogue, a binding regional treaty setting high‑level obligations for AI systems, and a growing body of human‑rights analysis targeted specifically at generative AI.

The practical relevance of these frameworks will vary: for organizations operating solely within the United States, the impact is indirect but growing; for those with international footprints, the obligations may become directly material. Either way, the question for cybersecurity, information‑governance, and eDiscovery professionals is less whether these instruments are perfect, and more whether internal AI‑enabled processes can be defended under their logic.

That means being able to show—not just assert—that AI tools are deployed in ways that respect dignity, minimize discriminatory impact, preserve the integrity of evidence, and provide realistic paths for redress when things go wrong. As enforcement approaches and litigation strategies evolve, the real test will be whether the AI systems embedded in your security stack, data‑governance workflows, and review platforms can be clearly explained, legally defended, and ethically justified—before regulators or courts ask.

News Sources

- Pact for the Future – United Nations Summit of the Future (United Nations)

- AI Panel and Dialogue (Global Digital Compact)

- Understanding the New UN Resolution on AI Governance (IPPDR)

- UNGA adopts terms of reference for AI Scientific Panel and Global Dialogue on AI governance (Digital Watch Observatory)

- The World’s First Binding Treaty on Artificial Intelligence, Human Rights, Democracy, and the Rule of Law: Regulation of AI in Broad Strokes (Future of Privacy Forum)

- Council of Europe Adopts International Treaty on Artificial Intelligence (Inside Privacy)

- Council of Europe Framework Convention on Artificial Intelligence and Human Rights, Democracy and the Rule of Law (Refworld)

- UN: The Global Digital Compact and AI governance (ARTICLE 19)

Assisted by GAI and LLM Technologies

Additional Reading

- Government AI Readiness Index 2025: Eastern Europe’s Quiet Rise

- Trump’s AI Executive Order Reshapes State-Federal Power in Tech Regulation

- From Brand Guidelines to Brand Guardrails: Leadership’s New AI Responsibility

- The Agentic State: A Global Framework for Secure and Accountable AI-Powered Government

- Cyberocracy and the Efficiency Paradox: Why Democratic Design is the Smartest AI Strategy for Government

- The European Union’s Strategic AI Shift: Fostering Sovereignty and Innovation

Source: ComplexDiscovery OÜ

ComplexDiscovery’s mission is to enable clarity for complex decisions by providing independent, data‑driven reporting, research, and commentary that make digital risk, legal technology, and regulatory change more legible for practitioners, policymakers, and business leaders.