Editor’s Note: Organizational change often begins with confronting the structures that no longer serve innovation. This article, grounded in on-the-ground reporting from a recent visit to Sillamäe, Estonia, during ComplexDiscovery’s coverage of the Latitude59 conference, explores the city’s dramatic transformation from Soviet-era secrecy to post-independence openness. Once a hidden node in the USSR’s nuclear network, Sillamäe now stands as a vivid case study in structural adaptation, cultural reintegration, and economic reinvention. For cybersecurity, information governance, and eDiscovery professionals, the city’s journey offers striking parallels to the modern challenge of dismantling organizational silos. It’s a reminder that rigid control, while once seen as a strength, must evolve to allow the flexibility and transparency essential for long-term resilience.

Content Assessment: The Architecture of Isolation: Cold War Cities and Corporate Silos

Information - 94%

Insight - 95%

Relevance - 90%

Objectivity - 92%

Authority - 92%

93%

Excellent

A short percentage-based assessment of the qualitative benefit expressed as a percentage of positive reception of the recent article from ComplexDiscovery OÜ titled, "The Architecture of Isolation: Cold War Cities and Corporate Silos."

Industry News – Technology Beat

The Architecture of Isolation: Cold War Cities and Corporate Silos

ComplexDiscovery Staff

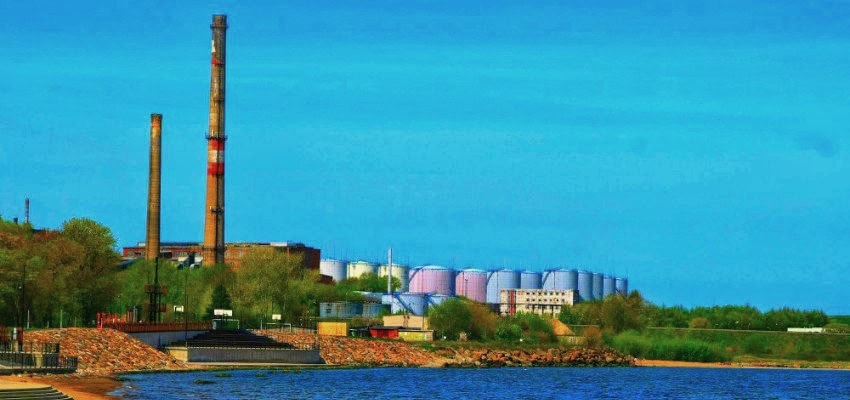

Estonia’s northeastern coastline harbors one of the most remarkable examples of Cold War secrecy and subsequent transformation in the former Soviet sphere. The city of Sillamäe, once erased from maps and known only by coded designations, represents a fascinating case study in information control, organizational isolation, and the eventual dismantling of barriers that separated communities from the outside world. Today, this former nuclear city serves both as a tourist destination and as a powerful metaphor for understanding how rigid organizational structures—whether in totalitarian states or modern corporations—can simultaneously protect and isolate, privilege and constrain.

The Genesis of a Secret City

Strategic Origins and Soviet Nuclear Ambitions

The transformation of Sillamäe from a peaceful Baltic resort town into one of the Soviet Union’s most closely guarded secrets began during the harsh winter of 1944-1945 when Moscow-based geologists arrived under military protection to investigate the uranium potential of Estonia’s oil shale deposits. The timing was no coincidence—as World War II drew to a close and the United States demonstrated the devastating power of atomic weapons at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Soviet leadership recognized that nuclear capability had become essential for maintaining superpower status.

The pivotal moment came during a high-level Kremlin meeting in the spring of 1945, where senior Soviet officials, including Beria, Voroshilov, and Malenkov—possibly even Stalin himself—examined a piece of Estonian slate and a three-liter jar of uranium concentrate. Voroshilov’s reported comment that “if it is necessary, uranium can be made from this clay” sealed Sillamäe’s fate as the cornerstone of the Soviet nuclear program. Within two years, the former resort town would be transformed into Factory #7, a designation that would define its existence for nearly half a century.

Constructing the Invisible City

The physical construction of Secret Sillamäe required an enormous mobilization of resources and labor, with an estimated 18,000 workers involved in the project by the end of 1946. The majority of this workforce consisted of soldiers and prisoners from the Gulag system, reflecting the Soviet practice of using forced labor for strategic projects. The town’s very existence became classified, reportedly assigned only the postal code “Mail Box #22” while its real address was forbidden from any correspondence.

The architectural approach to Sillamäe revealed the dual nature of Soviet secret cities—while isolated from the outside world, they were designed to provide superior living conditions for their inhabitants. The town was constructed according to Stalinist neoclassical principles, featuring grand boulevards, symmetrical buildings, and monumental public spaces that won the architectural premium of the Soviet ministerial council in 1949.

The Operational Reality of Secrecy

Life within secret Sillamäe operated according to strict protocols that governed every aspect of daily existence. The city was surrounded by security perimeters, requiring special permission for entry or exit. Residents enjoyed privileges unavailable elsewhere in Estonia—better housing, superior food supplies routed through Moscow, and access to scarce consumer goods. However, these material advantages came at the cost of fundamental freedoms, as inhabitants were forbidden from discussing their work or even revealing their place of residence to outsiders.

The demographic composition of Sillamäe reflected its specialized function, with highly educated technical specialists recruited from across the Soviet Union. By 1989, the overwhelming majority of residents spoke Russian as their primary language, illustrating how the secret city system fundamentally altered the ethnic and cultural landscape of northeastern Estonia. This linguistic and cultural isolation would persist long after Estonian independence, creating lasting social and political challenges.

From Nuclear Weapons to Rare Earth Elements

The End of the Secret Era

The dismantling of Sillamäe’s secret status began gradually during the late 1980s as Mikhail Gorbachev’s glasnost policies loosened information controls throughout the Soviet Union. Uranium production officially ceased in 1990, one year before Estonia’s restoration of independence, marking the end of an era that had produced over 100,000 tons of uranium for an estimated 70,000 nuclear weapons.

Estonia’s declaration of independence on August 20, 1991, finally opened Sillamäe to the outside world after 44 years of enforced isolation. The transition brought both opportunities and challenges—the city faced economic uncertainty, environmental contamination, and questions about the future of its specialized workforce. However, the foundation of technical expertise and industrial infrastructure proved valuable for the post-Soviet economy.

Contemporary Transformation and Economic Adaptation

Modern Sillamäe has successfully reinvented itself while preserving its unique architectural heritage and industrial capabilities. The former uranium facility was privatized in 1997 and transformed into Silmet, now owned by Toronto-based Neo Performance Materials, which processes rare earth elements essential for modern electronics and green energy technologies. This economic transition represents a remarkable transformation from weapons production to civilian technology, with the facility now processing up to 8,000 tons of rare earth materials and 2,000 tons of niobium annually.

The city’s population has stabilized at approximately 12,000 residents, down from its Cold War peak of around 20,000. While population decline has been a concern, new investments are bringing hope for renewal—a €6 million EU-funded hotel project aims to transform a Soviet-era administrative building into a boutique accommodation, reflecting growing interest in Sillamäe’s unique history and architecture.

Environmental remediation has been a major success story, with a €21 million project (330 million kroons) completed in 2008 to secure 12 million tons of radioactive waste that had accumulated during the uranium processing years. The waste, which once posed a serious threat to the Baltic Sea ecosystem, is now safely contained behind concrete barriers and covered with protective layers.

The Architecture of Isolation: Secret Cities and Corporate Silos

Structural Parallels in Information Control

The organizational principles that governed Soviet secret cities offer striking parallels to the communication silos that plague modern corporations. Both systems emerge from similar imperatives—the need to control sensitive information, maintain operational security, and preserve competitive advantages. However, both also demonstrate how protective measures can evolve into counterproductive barriers that stifle innovation and adaptability.

In secret cities like Sillamäe, information flowed vertically through strict hierarchical channels directly to Moscow, while lateral communication between cities was severely limited or prohibited entirely. Modern corporations often exhibit similar patterns, with departments sharing information upward to senior management while maintaining limited cross-functional communication. This vertical orientation creates what researchers term “silos”—isolated organizational units that operate with minimal coordination or knowledge sharing.

The Psychology of Privileged Isolation

Both secret cities and corporate departments often develop what scholars call “silo mentality”—a mindset that views information sharing as potentially threatening to group status or resources. Residents of Sillamäe enjoyed material privileges unavailable to other Estonians, from better housing to superior consumer goods. Similarly, corporate departments often guard their budgets, expertise, and access to senior leadership as sources of organizational power.

This privileged isolation becomes self-reinforcing as groups develop internal cultures and practices that further differentiate them from the broader organization. The predominantly Russian-speaking population of Sillamäe maintained distinct cultural practices and communication patterns that persisted long after Estonian independence. Corporate departments similarly develop specialized vocabularies, processes, and cultural norms that can make cross-functional collaboration challenging.

Physical and Digital Barriers

The physical barriers that surrounded secret cities—barbed wire, checkpoints, and restricted access zones—find modern equivalents in corporate environments through separate office locations, restricted access systems, and proprietary software platforms that don’t integrate across departments. Just as Sillamäe residents required special permission to enter or leave their city, modern employees often need specific credentials or approval to access information systems or attend meetings outside their immediate functional area.

Breaking Down the Walls: Lessons for Modern Organizations

The Costs of Compartmentalization

The secret city system ultimately proved unsustainable not because of external pressure but because of its inherent inefficiencies and inability to adapt to changing circumstances. The rigid compartmentalization that protected sensitive information also prevented the innovation and flexibility necessary for long-term success. Modern organizations face similar challenges when departmental boundaries become barriers to customer service, product development, or market responsiveness.

Strategies for Sustainable Openness

Sillamäe’s successful transition suggests several principles for organizations seeking to reduce harmful silos while maintaining necessary boundaries. First, change must be gradual and carefully managed to preserve valuable capabilities and relationships. Second, new structures must provide clear benefits to participants, just as modern Sillamäe offers tourism opportunities and environmental improvements alongside continued industrial employment. Third, external accountability and transparency can provide motivation for internal reforms.

The transformation of Sillamäe’s uranium facility into a rare earth processing plant demonstrates how organizations can leverage existing capabilities while adapting to new market requirements and regulatory environments. This evolution required preserving valuable technical expertise while fundamentally changing operational structures and external relationships.

From Isolation to Integration

The story of Sillamäe represents more than historical curiosity—it offers a compelling case study of organizational transformation and the evolution from secrecy to transparency. The city’s journey from nuclear weapons production to rare earth processing, from enforced isolation to tourism destination, demonstrates that even the most rigid organizational structures can adapt and thrive when barriers are thoughtfully dismantled.

For modern organizations struggling with communication silos, Sillamäe’s experience suggests that change is both possible and necessary for long-term sustainability. The key lies in recognizing that while some boundaries serve legitimate purposes, excessive compartmentalization ultimately weakens rather than strengthens organizational capacity. Like the residents of Sillamäe who finally emerged from decades of isolation to engage with the broader world, organizations must find ways to balance necessary confidentiality with the collaboration and knowledge sharing essential for innovation and growth.

The architectural monuments of Stalinist Sillamäe remain as reminders of an era when information control seemed paramount to national security. Today, as the city welcomes visitors to walk its grand promenades and explore its unique history, it stands as a testament to the possibility of transformation—from secrecy to openness, from isolation to integration, from the rigid hierarchies of the past to the collaborative networks necessary for future success.

News Sources

- Estonian Statistical Office. “Population Statistics – Sillamäe City.” Statistics Estonia, 2021. https://www.stat.ee

- City of Sillamäe. “General History.” Official Website of Sillamäe, accessed Jun. 2025. http://www.sillamae.ee/web/eng/general-history

- City of Sillamäe. “Secret Period.” Official Website of Sillamäe, accessed Jun. 2025. http://www.sillamae.ee/web/eng/secret-period

- International Atomic Energy Agency. “IAEA Mission Says Estonia Committed to Safe Management of Radioactive Waste.” IAEA Press Release, April 3, 2019. https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/pressreleases/iaea-mission-says-estonia-committed-to-safe-management-of-radioactive-waste-sees-areas-for-further-enhancement

- European Environment Agency. “Estonia Country Briefing – The European Environment.” EEA Report, March 28, 2014. https://www.eea.europa.eu/soer/2015/countries/estonia

- Ministry of Environment, Estonia. “National Programme for Radioactive Waste Management.” Government of Estonia, 2016. https://www.nuclear-transparency-watch.eu/htdocs/wp-content/uploads/2016/NaProESTONIA.pdf

- Neo Performance Materials. “Neo Announces Operational Transformation at Estonia Rare Metals Facility.” Company Press Release, December 15, 2023. http://www.neomaterials.com/neo-announces-operational-transformation-at-estonia-rare-metals-facility/

- City Population Database. “Sillamäe (Ida-Viru, Settlements, Estonia).” de, 2021 Census Data. https://www.citypopulation.de/en/estonia/ua/ida_viru/L028__sillam%C3%A4e/

Assisted by GAI and LLM Technologies

Additional Reading

- Castles, Borders, and the Battle for Cyberspace

- “Bee vs. Elephant”: Estonia’s Agile Strategy Headlines Latitude59

- Strategic Innovation and Ukraine’s Tech Frontline at Latitude59 and Dublin Tech Summit

Source: ComplexDiscovery OÜ